“Today, that peace, that stability and our continued success have come under threat. Once again, we must come together as partners to face the common challenges confronting the region,” he said. “Not one single country can do this by itself, no single force can attend, counter them, by themselves.”

Filipino envoy says South China Sea is the ‘real flashpoint’ in Asia, not Taiwan

Filipino envoy says South China Sea is the ‘real flashpoint’ in Asia, not Taiwan

Marcos Jnr’s comments were symbolic, said Bjorn Dressel, director of the Australian National University’s ANU Philippines Institute.

Alongside collaboration on military patrols, he said the Philippines also valued having other countries such as Australia and the US step up to fend off unacceptable acts of aggression in the South China Sea.

“For international law to be respected, you rely on other state actors to lend you support whenever there is a violation,” Dressel said.

South China Sea code: Philippines’ U-turn a sign tensions still hinder progress

South China Sea code: Philippines’ U-turn a sign tensions still hinder progress

Asia-based academic Richard Heydarian said it was clear Marcos Jnr was serious about growing a strategic relationship with Australia, especially given the lull in their ties over recent years.

Duterte also criticised Australia for meddling in Filipino affairs by condemning his anti-drug campaign that led to more than 6,000 extrajudicial killings.

He pointed out that Malaysia remained “fiercely independent” even as the region found itself under increasing pressure to pick sides between China and the US.

“If they have problems with China, they should not impose it upon us,” Anwar said. “We do not have a problem with China.”

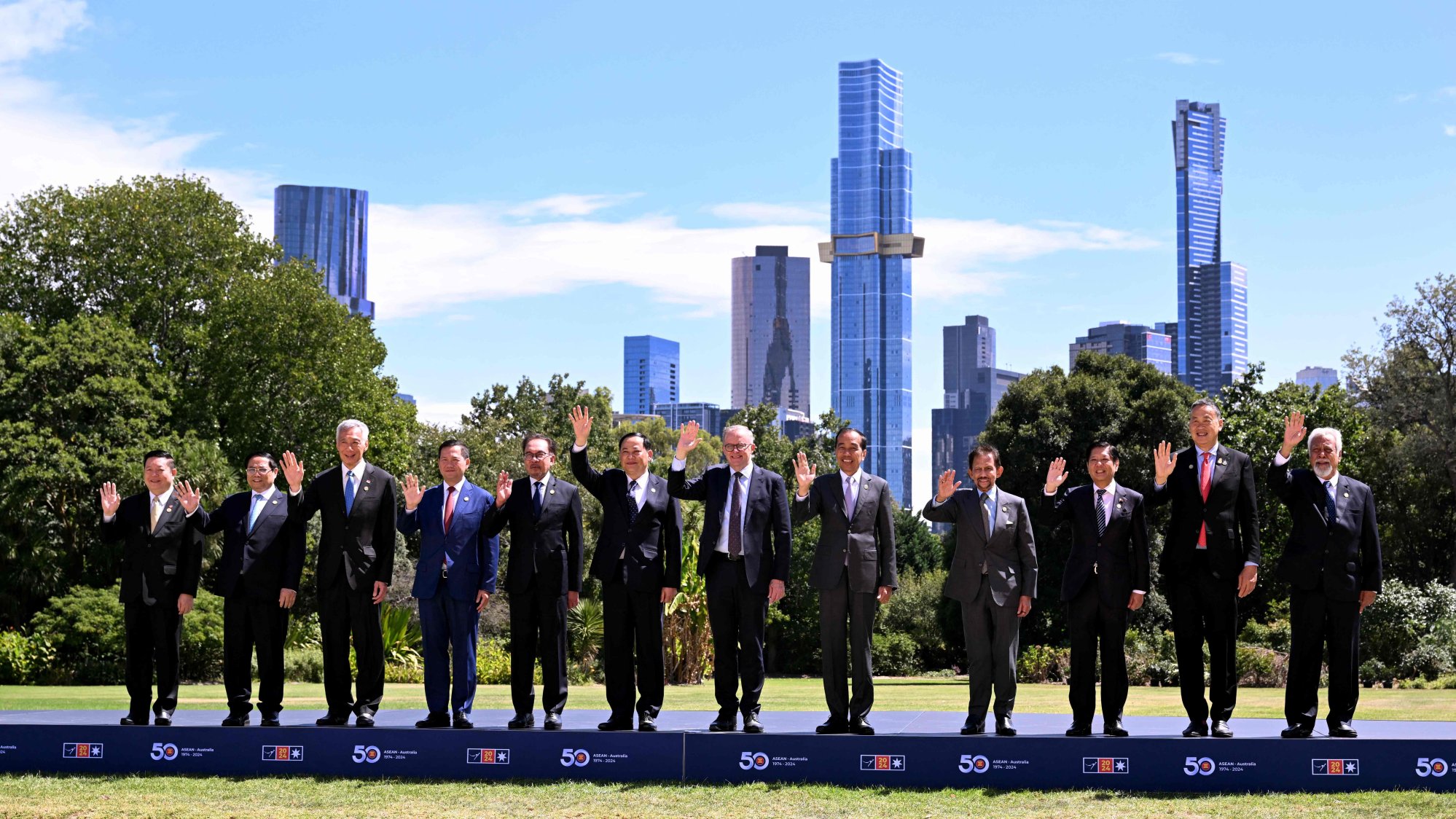

‘We face coercive actions’: Australia offers Asean millions for maritime security

‘We face coercive actions’: Australia offers Asean millions for maritime security

Don McLain Gill, an international-studies lecturer at De La Salle University in the Philippines, said Manila’s “robust” foreign policy of deepening and broadening its security ties, with partners in the region and beyond, was aimed at strengthening its maritime security and defence capabilities.

“[It’s] also to ensure that the South China Sea remains open and rules-based.” Such a position would “inevitably upset China”, Gill said, and raise concerns among other Southeast Asian nations that are ambivalent about external powers’ growing military presence.

“However, it must be understood that even if Manila’s position was not as robust as it is now, China would continue to pursue its narrowly driven security interests in the region,” he said. “Thus, Manila has realised the need to become more proactive in seeking options to address this challenge.”

Jagannath Panda, head of the Stockholm Centre for South Asian and Indo-Pacific Affairs, said that amid Manila’s naval skirmishes with Beijing in the South China Sea, its strategic ties with Canberra helped the Philippines strengthen its contacts with Australia’s other Western allies.

“Solidifying strategic contacts with Australia does help Manila to gather and share enough timely information on China’s maritime activities,” Panda said.

‘Strategic complementarity’

“Japan, Australia and India figure highly in the Philippines’ maritime security strategy,” Panda said, especially in maritime security and deterrence against Chinese maritime advance.

The 2016 verdict refers to the Hague-based court, which ruled in favour of the Philippines and determined that major elements of Beijing’s claim – including land reclamation activities in the South China Sea – were unlawful.

“A strategic complementarity has been building between India, Japan, and the Philippines for some time now,” Panda said, adding that the nations also shared a posture of “revisionism resistance” vis-à-vis China’s attempts to change the status quo.

Though a formal strategic trilateral between India-Japan-Philippines is yet to be established, such a trilateral is very much a practical proposition

The Philippines said in January that it hoped to sign an agreement with Japan by March allowing the deployment of military forces on each other’s soil.

The Philippines and India are also looking to step up defence ties after Philippine foreign minister Enrique Manalo visited last year.

As well as upgrading interactions among defence officials, they plan to open a resident defence attaché office in Manila and expand joint maritime training and exercises.

“These three non-Western countries have been quite vocal against China, questioning the authoritarian revisionist practices China is pursuing in both the land corridors and maritime corridors,” Panda said.

“Though a formal strategic trilateral between India-Japan-Philippines is yet to be established, such a trilateral is very much a practical proposition.”

“The evolution of these partnerships will be fuelled by Chinese behaviour. A more conciliatory Beijing will see less cooperation between various countries, [while] a more assertive Beijing will push these countries together,” he said.